Rebalancing Healthcare Services and the "Capability Trap": A Systems View

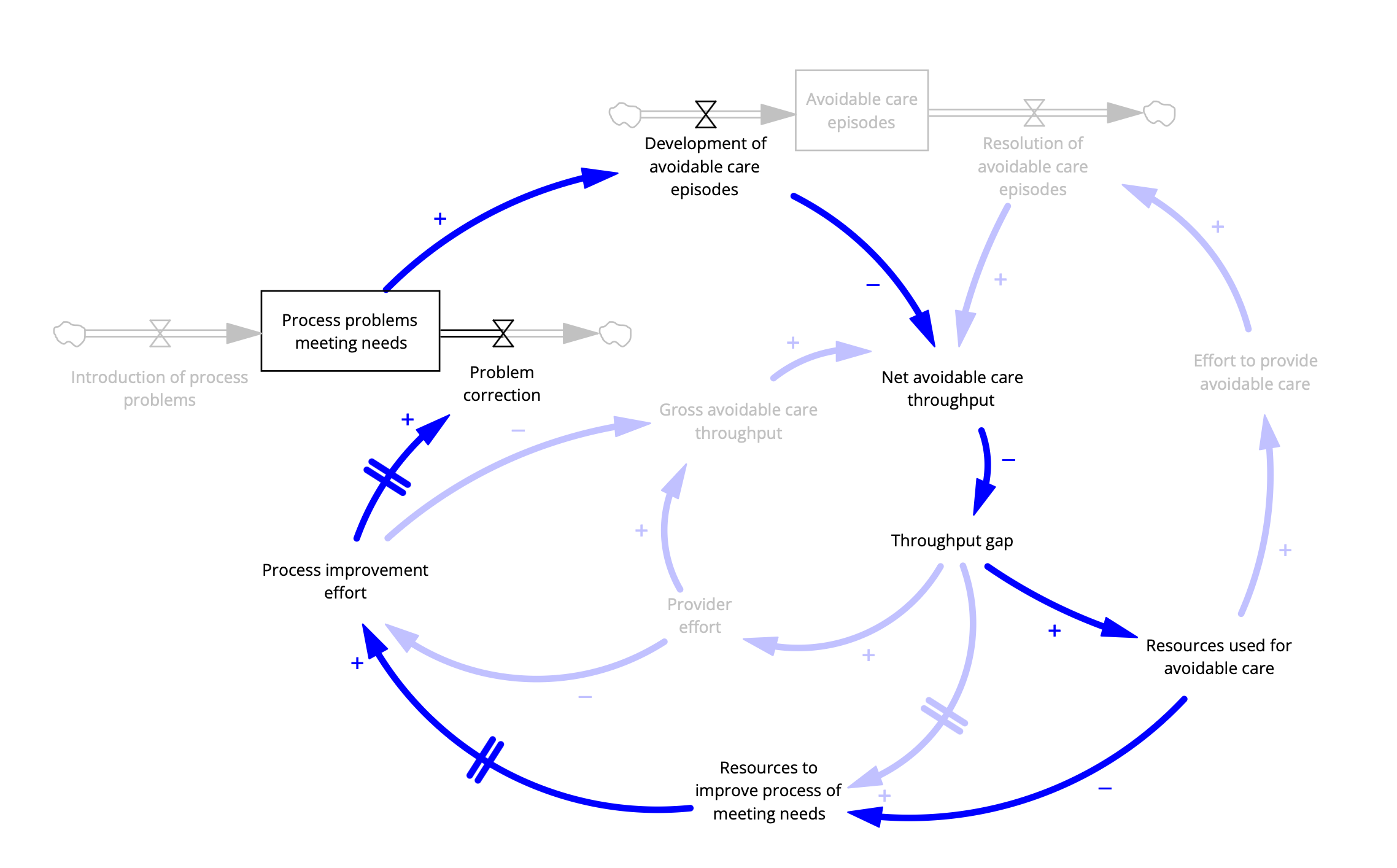

The capability trap applied to healthcare. Based on Sterman, 2002, thanks to Prof. Peter Hovmand, Case-Western.

This brief post provides an example of a systems thinking method used in System Dynamics, the Stock and Flow Diagram. Here it’s applied to the phenomenon described in my last post, “sizzle then fizzle” (innovation that fails before it has a chance to succeed), also known as the “capability trap”.

With populations aging rapidly and the associated increase in complexity of health and social care needs, the necessity of rebalancing healthcare resources towards primary and community care is undeniable. To effectively manage these emerging health demands, services must become better coordinated, with greater emphasis on preventive care, palliation, and community-based interventions. Indeed, our research team has demonstrated through simulation experiments that enhancing primary and community care can significantly reduce unnecessary hospitalizations, improve health outcomes, and extend healthy life expectancy.

Yet despite these clear benefits, meaningful rebalancing remains elusive.

What we see today is growing recognition of the value of an accountable point-of-care—typically a primary care physician (PCP)—who identifies, meets, or coordinates patient needs through onsite care or timely referrals to other providers. A robust primary care system would integrate preventive care, acute care management, chronic disease control, mental health services, and social determinants of health into a cohesive, patient-focused strategy. However, as emphasized in previous discussions, the current structure and staffing of most primary care practices simply cannot meet these comprehensive demands. In short, PCPs face overwhelming workloads without sufficient capacity, resources, or coordination support.

Given this reality, why not invest more substantially in primary care infrastructure? Why not significantly raise PCP compensation—which currently trails far behind that of specialists—to incentivize careers in primary care? Why not expand primary care teams by integrating non-physician clinicians who can deliver standardized, guideline-based care and free PCPs to handle more complex issues? Furthermore, why not develop comprehensive, integrated medical records that bridge medical and community services to ensure coordinated, continuous patient-centered care?

Several factors contribute to this inertia. In the context of a broad range of improvement programs, both public and private, management theorists suggest that it could be behavioral bias (specialty and hospital services are much cooler than dull as dishwater primary care services). It may be that policy makers disbelieve the benefits to whole system performance (if primary care was that good it would have already been prioritized) or it could be lack of capital (I’d like to invest in primary care, but if we have cash, we need to use it for urgent short-term needs).

However, another powerful systemic barrier—often overlooked—is the phenomenon known as the "capability trap", a term coined by systems thinker John Sterman. The capability trap arises when organizations consistently divert resources from building long-term capabilities (such as preventive and community-based care needs) to address immediate performance pressures (like acute hospital demands). Over time, this short-term reactive cycle erodes the very capabilities needed to achieve long-term performance, creating a reinforcing feedback loop that entrenches chronic underinvestment in foundational services.

A more detailed description of the feedback loops involved at the end of this post.

In healthcare, this trap manifests clearly: hospitals and specialist services, facing urgent short-term pressures, attract resources away from primary and community care investments. The weaker primary care becomes, the greater the demand on specialist and acute care services—perpetuating the cycle. Breaking free of this capability trap requires intentional, sustained investment in primary care infrastructure, workforce development, and service coordination despite immediate pressures.

A systems perspective thus clearly reveals the necessity—and the difficulty—of rebalancing healthcare. Making this shift requires not only recognizing the long-term value of primary and community care but also systematically addressing and disrupting the reinforcing feedback loops that underpin the capability trap itself.

The Stock and Flow diagram shown here again represents a dynamic causal hypothesis in which the “capability trap” theory is applied to healthcare.

Notation

Boxes represent measurable features of the system that accumulate and diminish over time (like water in a bathtub).

Double arrows with a “valve” are flows into and out of stocks (like faucets and drains). These flows are influenced by features that change over time and the single arrows represent causal statements: the entity at the tail of the arrow causes an increase or decrease in the entity at the arrowhead, all other things being unchanged.

The polarity of the relationship is reflected by a “+” or “-” sign adjacent to the arrow. If the sign is “+” then if the entity at the arrow tail increases then the entity at the arrow head increases (again ceteris paribus, for you Latin lovers).

Many of the arrows together form loops, such that one can start at one entity and follow a trail of arrows back to the same entity. These loops can be reinforcing loops (that is, an increase in the entity is further enhanced by the cause and effect chain of the loop. Or they can be inhibiting loops (or balancing) in that the loop’s effect is to suppress further increases in the entity.

Finally, arrows crossed by a double line in the middle denote that the effect has a delay.

Simplifying assumptions. The basic notion is that a well-functioning healthcare system identifies and meets needs that reduce the risk of avoidable healthcare problems. These problems are manifest as avoidable episodes of care (what would be considered a “defect” in the manufacturing context).

Reviewing the salient loops

With regard to the capability trap, there are several relevant loops. The simplest to see is at the right of the diagram.

The Rework Loop

The “Rework Loop” represents the effort that must be applied to address an avoidable episode such as a rehospitalization that occurs as a result of early discharge to a primary care provider without the capability to manage post-acute care. Starting with “Net avoidable care throughput” (the difference between the development and resolution of avoidable care episodes), when that is bad (low) the loop dynamic creates a balancing effect: low throughput leads to an increase in performance gap leads which leads to and increased allocation of resources to those immediate problems and greater effort to provide care, more rapid resolution of episodes and increase in net avoidable care throughput. This is the same dynamic that applies to manufacture rework of defects, or attention to bailing rather than repairing when faced with a leaking boat.

A similarly short loop is the “Working Harder” loop in which higher expectations are not matched by greater resources:

The Work Harder Loop

Here, in response to a reduction in net avoidable care throughput (that is there are an excess of avoidable care episodes such as those due to failure to meet mental health needs), the perceived gap is addressed by increasing provider effort: increasing care slots by reducing appointment length or extending hours, and so on. This will lead to increased throughput, but at a cost to provider satisfaction.

Now the more complex loops that relate to the capability trap: Focus on the loops that include “Development of avoidable care episodes”.

The loop we’d like to have is the one that will tend to reduce that rate, and thus alleviate the need for rework (with resources) or working harder (without new resources):

The Working Smarter Loop

In this balancing loop, “Working Smarter” an increase in the rate of avoidable care episodes reduces net throughput. In response to the resulting gap, resources are allocated to improve care process, which leads to greater effort to make fundamental process improvements, leading to an increase in rate of process problem correction, fewer unmet needs and ultimately fewer episodes of avoidable care episodes.

Nice.

But notice that there are 3 causal arrows with delays, which means that this “Working Smarter” loop takes time: time to allocate resources, to initiate concrete efforts and for those efforts to bear fruit.

In the meantime, there is another loop that is working against process improvement efforts.

The Competition Between Short- and Long-term Needs Loop

Follow the loops and the problem becomes apparent: more avoidable care episodes requires a response by administrators to allocate more resources to address the urgent problem.

Note that there are several other loops that influence the effort to broadly improve health system performance. Indeed, there are 6. I leave these to the reader to discover.